Articles and Publications

Part 2: Off-Target: Dicamba Drift Issues Ensnaring Farmers

August 15, 2017

Recently, issues surrounding the use and regulation of dicamba have been dominating the landscape of agribusiness news. Packaged as a solution to the growing “super weed” problem facing farmers throughout the U.S., the coupling of glyphosate/dicamba-tolerant seeds with newly formulated dicamba-based herbicides has seemingly presented as many challenges as it was presented to solve. Over the past twelve months, farmers, industry experts, and state agencies have dealt with drift complaints increasing at an exponential pace, class action lawsuits being filed against the seed and spray manufacturers (with more litigation on the way), and even an alleged murder. This is part two of a two-part article that takes a comprehensive look at how we got here, a broad overview of current dicamba-related issues, and what we can expect to see in the future.

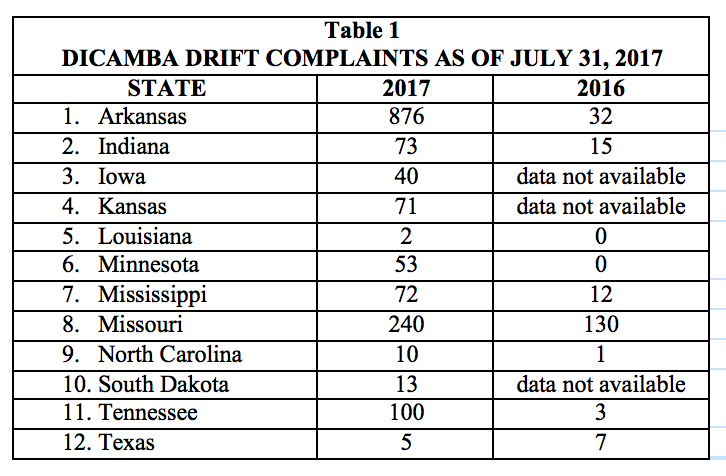

Dicamba-Drift Complaints, by State

This year has seen a startling increase in complaints made by farmers to state agencies, whereby farmers are contending that dicamba sprayed by their neighbors onto their crops have drifted onto the complaining farmer’s crops. The complaining farmers allege that this drift has caused damage to their crops, though the extent of the damage cannot be measured until harvest. Our firm has been tracking and processing this data on a state-by-state basis. Table 1, below, shows the complaints fielded by various states through July 31, 2017, as compared to complaints received throughout all of 2016. The data shown was procured through either online public records or from Freedom of Information Act requests submitted by our firm.

State Agencies Respond

Due to the stark increase in dicamba-related complaints, and based on state scientists’ observations of drift impacts, certain states have taken swift and decisive action with regard to the use of dicamba in over-the-top application. Arkansas – the state with the most reported complaints, by far – took the most drastic measure on July 7 by temporarily banning the use and sale of dicamba products in the state for 120 days. The temporary ban was approved through a vote by the Arkansas House and Senate Committee on Agriculture, Forestry and Economic Development, and went into effect on July 11 at 12:01 a.m. After that time, farmers caught in violation face a $1,000 fine; after August 1, the fine increases to $25,000. The committee will meet again in November to consider extending the ban. Monsanto responded to the temporary ban by issuing the following statement: “We sympathize with any farmers experiencing crop injury, but the decision to ban dicamba in Arkansas was premature since the causes of any crop injury have not been fully investigated. While we do not sell dicamba products in Arkansas, we are concerned this abrupt decision in the middle of a growing season will negatively impact many farmers in Arkansas.”

Missouri, the state with the second-most dicamba-related complaints, has also taken swift action in response to the industry’s growing fears. Only July 7, 2017 – the same day that Arkansas enacted its temporary ban – the Missouri Department of Agriculture also halted the sale or use of any dicamba products marketed for agricultural use through the issuance of a Stop Sale, Use or Removal Order. However, on July 13, 2017, citing agreements with BASF, Monsanto, and DuPont, the Missouri Department of Agriculture issued a Notice of Release from the statewide Stop Sale, Use or Removal Order for ENGENIA Herbicide; XTENDIMAX with VaporGrip Technology; and FEXAPAN™ Herbicide Plus VaporGrip™ Technology. The Notice of Release was issued after the Department approved a Special Local Need label for each herbicide that included provisions and additional safeguards relating to wind speed, timing of application, certified applicator training, notice of application and additional record-keeping requirements for the use of these specific herbicides.

On July 12, 2017, the Tennessee Department of Agriculture similarly strengthened its previously enacted regulations concerning dicamba.The new regulations currently extend through October 1, 2017, and impose heightened requirements on farmers and applicators. For example, applicators must be certified and follow certain record-keeping requirements, spraying hours are shortened to between 9:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m., applicators must avoid temperature inversions, and the use of the older dicamba formulations is prohibited, as is over-the-top application on cotton after first bloom.

In Indiana, the Pesticide Rule Board has begun the process to classify agricultural-use dicamba as a Restricted Use Pesticide. Included in this classification would be any formula containing 6.5% or more of dicamba. The proposed rule is slated to become effective in 2018.

Current Litigation

Our firm’s national litigation team has been monitoring the issues discussed above as they have made their way into the Courts. The first lawsuit growing from the introduction of dicamba-tolerant seeds surfaced in November of 2016: Bader Farms, Inc., et al v. Monsanto Company, Case No. 16DU-CC00111, filed in Dunklin County, Missouri, but subsequently removed to federal court in the Eastern District of Missouri (Case No. 1:16-cv-00299). In this lawsuit, Bill Bader of Bader Farms in Campbell, Missouri filed suit against Monsanto claiming that more than 7,000 peach trees were damaged by drift from neighboring farmers’ illegal spraying of the old dicamba formulation in 2015, resulting in $1.5 million in damages. Mr. Bader further alleged that the damages suffered in 2016 were worse – 30,000 trees, with damages in the multi-millions.

Mr. Bader alleged that Monsanto knowingly released its dicamba-tolerant soybean and cotton seeds on the market prior to the EPA approving the new dicamba formulation that the seeds were marketed to be used in conjunction with. Mr. Bader alleged that, despite Monsanto’s written warnings advising against the use of off-label dicamba on its new dicamba-tolerant seeds, Monsanto did not do enough to warn farmers of the risk and/or Monsanto knew that farmers would illegally use off-label dicamba with the new seeds. Mr. Bader makes claims of strict liability for Monsanto’s alleged design defects and failure to warn, negligent design and marketing, negligent failure to warn, negligent training, breach of implied warranties, fraudulent concealment, unjust enrichment, and seeks punitive damages.

On December 30, 2016, after removing the case to federal court, Monsanto filed a Motion to Dismiss the lawsuit, claiming that the neighboring farmers’ illegal spraying of the off-market dicamba was a superseding and intervening cause of the Plaintiffs’ injury that Monsanto could neither foresee nor control. In light of this argument, the Plaintiffs amended their Complaint to allege that Monsanto representatives actually directed and encouraged farmers to use the not-yet-approved dicamba on Monsanto’s already-available dicamba-tolerant seeds. On June 29, 2017, the Court sided with the Plaintiffs, holding that this new allegation, if taken to be true, was sufficient to defeat Monsanto’s Motion to Dismiss. Plaintiffs’ counsel is Randles and Splittgerber from Kansas City, while Thomspon Coburn, LLP, from St. Louis represents Monsanto.

Indeed, as our litigation team knows all too well, once an initial lawsuit involving issues of this scope gains traction, a class action lawsuit is likely to follow. The first class action lawsuit relating to dicamba drift subsequently was filed by the same group of plaintiff lawyers – Randles and Splittgerber – in the Eastern District of Missouri in February 2017: Steven W. Landers, et al. v. Monsanto Company, Case No. 1:17-cv-00020 (E.D. Mo.). The named plaintiffs in the Landers lawsuit – Steven and Deloris Landers – purportedly filed their lawsuit on behalf on behalf of themselves and similarly situated farmers in ten different states (Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas). The factual allegations and legal claims in Landers mirror those made in Bader Farms, all related to Monsanto’s release of dicamba-tolerant seeds prior to the release of the new dicamba formulations, and the plaintiffs’ damages from dicamba drift. As with the first case, Monsanto is represented in Landers by Thompson Coburn.

On June 14, 2017, a second class action lawsuit was filed in Arkansas, but this time against both Monsanto and BASF: Bruce Farms Partnership, et al. v. Monsanto Company, BASF SE, BASF Corporation; E.D. Ark. 3:17-cv-00154-DPM. The claims in Bruce Farms not only encompass the issues raised in Bader Farms and Landers concerning the timing of Monsanto’s release of the dicamba-tolerant seeds versus the dicamba spray, it also makes the claim that dicamba sprays, as a whole, “cannot be applied with reasonable safety,” making the seeds and sprays inherently dangerous products. Claims raised in the Bruce Farms lawsuit include strict liability, negligence, breach of implied warranties, violation of Arkansas’s Deceptive Trade Practices Act, fraud and fraudulent concealment, unjust enrichment, and civil conspiracy, and seeks punitive damages. Bruce Farms was filed by the Duncan Firm, the Kelly Law Firm, and the Paul Byrd Law Firm; at the time of publication, the Defendants have yet to respond.

Then, on July 19, 2017, a new class action lawsuit was filed in Missouri raising new theories of liability: Smokey Alley Farm Partnership et al. v. Monsanto Company et al.; in the Eastern District of Missouri, Case No. 4:17-cv-2031. In this new lawsuit, the plaintiffs sued all of the dicamba formulation manufacturers – Monsanto, DuPont, and BASF – alleging these companies have engaged in anti-trust behavior in their mass roll-out of dicamba products. In addition to claims relating to the damage alleged caused by dicamba drift, the plaintiffs allege that drift resulting from off-label use of dicamba (and even from the correct application of dicamba) actually helps these companies in that it forces all farmers to use the tolerant seeds as a defense mechanism, if nothing else. Included in the plaintiffs’ allegations are claims under the Lanham Act and the Sherman Act as well as claims for negligence, trespass, public nuisance, products liability, ultra-hazardous activities, failure to warn, and under Arkansas’s Deceptive Trade Practices Act. The plaintiffs are represented by the St. Louis law firm of Peiffer Rosca, LLP, and the Little Rock law firms of Dover and Dixon, PLLC and James and Carter, LLP; DuPont, the only defendant entering an appearance at the time of publication, is being represented by Lightfoot and Franklin from Birmingham, AL.

As our litigation team well knows, civil claims are not the sole avenue to court for those affected by dicamba drift. On October 27, 2016, Mike Wallace of Monette, Arkansas was killed, allegedly during a dispute over dicamba drift. Wallace, who was unarmed, was shot and killed by Allan Curtis Jones of Arbyrd, Missouri. Wallace previously had reported Jones’ boss to the regulatory authorities for illegally spraying dicamba, an act which Wallace believed had damaged his own soybean crop. Jones’ first-degree murder trial is currently set for September 2017 in Mississippi County, Arkansas Circuit Court.

What to Expect Moving Forward

Our firm’s analytics team has been tracking online activity related to dicamba, as these issues have been developing. Trends indicate that as farmers approach harvest and as complaints submitted to various state agencies continue to increase, interest in potential litigation is piquing. For example, from July 8, 2017 to July 14, 2017, our analysis of search engine activity indicates that searches for “dicamba lawsuit” increased by 35% over the prior week. Then, the following week, searches again increased by 52%. Similarly, we saw a 233% increase in queries for “dicamba drift” between July 5, 2017 and July 11, 2017. While Arkansas and Missouri remain the epicenter for online research related to dicamba-related claims, Tennessee, Mississippi, and North and South Dakota show significant online activity investigating these issues.

Not surprisingly, with significant crop damage being reported, it is easy to find advertisements online soliciting class action and individual lawsuits. Farmers affected by dicamba drift have several potential avenues of recovery: claims against the dicamba-tolerant seed manufacturer, the manufacturers of the various dicamba herbicide products, and their neighboring farmers – those who sprayed dicamba off-label and potentially even those who sprayed according to manufacturer instructions – for common law torts such as negligence, trespass, and nuisance. Claims are also conceivable against third-party applicators and manufacturers of application equipment and apparatus. Claims are possible even if the neighboring farmers’ crops survive the drift impact if the buyers choose to reject any crop due to the unintended exposure. In fact, claims could be made by farmers who used the new dicamba formulas against the manufacturers for failure to warn or for negligent misrepresentation, and if dicamba formulations are banned, like they were in Arkansas, claims could exist for having bought unusable technology and products. Finally, claims may fit within various states’ consumer protection statutes, which typically contain stiff civil penalties to be levied per violation.

The level of crop damages to be suffered by farmers this year is unknown, and cannot be accurately assessed until the conclusion of harvest when this year’s yield can be compared to previous yields. While loss of yield is the most obvious measure of damages, the spectrum of potential damages and theories of liability and recovery, much like the future of dicamba, remains uncertain.

Explore

related services

Etiam porta sem malesuada magna mollis euismod. Nullam quis risus eget urna mollis ornare vel eu leo. Vestibulum id ligula porta felis euismod semper.